Mobile Scareware – Bringing Scary Back (Social Engineering Ep. 3)

With this entry, we continue our series on common methods of social engineering that target mobile devices. This time around, we discuss “Scareware”.

For our first post, on Malicious Mobile Advertising

For our second post, on Fake Apps

How Does a Scareware Attack Work?

Scareware attacks are based on the victim initiating the download of malware after receiving some form of fake message or notification, falsely alerting them that their device is infected and requires “a security app”.

These notifications typically use mobile advertising platforms in order to present themselves to the user. Depending on the quality of the attack, the ad might look just like a message from one of the familiar Anti-Virus (AV) vendors or in some of the more advanced cases, the alert can look just like an Android or iOS notification.

Attackers leverage ads as a form of legitimacy. If a notification originates from a trusted site, and especially when it looks like it has been generated by the OS or one of the installed apps, it makes it a lot easier to trick victims into believing it.

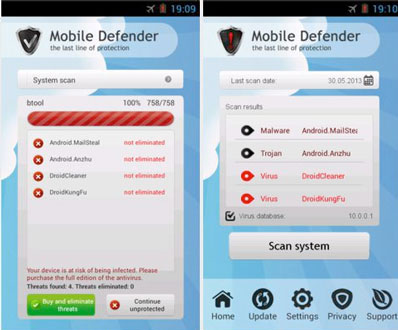

Once the victim downloads the fake app or initiates the fake virus scan, the victim is often shown a fake progress bar that helps establish the legitimacy of the original scam. The result? The victim is always “infected” by a range of different malware – further enabling the attacker to implement more scareware tactics.

What are the Consequences of a Scareware Attack?

The negative effects usually fall into one of two categories:

- The scareware deceives users into paying for cleanup of non-existent infections on their device. Ultimately the scareware ends up as a download that just doesn’t do anything.

Android Defender was an attack based on exactly this method.

Available on quite a few third party market places, Android Defender was an app that both pretends to scan for malware and pretends to find several malicious files, before pressuring the user into buying the full version to get rid of the “dangerous findings”.

- The scareware deceives users into downloading and installing malware (thinking it’s an AV app)

As we’ve mentioned in many of our previous blog posts, there are a vast range of consequences that can arise from a mobile device being infected with malware. Depending on how advanced the malware itself is the attacker can:- Sign the victim up to a premium SMS service.

- Begin using the victim’s device to mine cryptocurrency

- Install an advanced mRAT (Mobile Remote Access Trojan) to retrieve the victim’s personal and corporate data and passwords, record meetings and take pictures, relaying them to the attacker’s server.

-

The fact that the victim believes the malware to be an AV (or equivalent) app, often causes them to grant the malicious app with all the permissions and access that it requests. This just makes the whole process even more attacker-friendly.

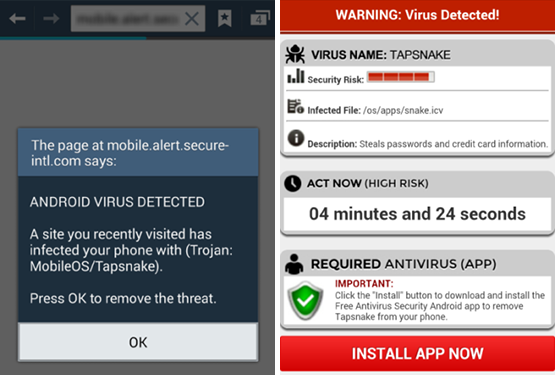

A good example of this kind of attack is MobileOS/Tapsnake

This scareware campaign used several mobile ads that attempted to scare users into downloading a fake AV app, believing their device had been infected by an mRAT (Mobile Remote Access named MobileOS/Tapsnake.

This specific attack was especially clever – the fake virus warning was made a little more believable due to the fact that there really was a piece of Android malware called Tapsnake, which was first spotted in 2010.

In some versions, the fake app eventually signed the victim up to a premium SMS service, while in others the fake app demanded payment for a full removal of the non-existent infection.

-

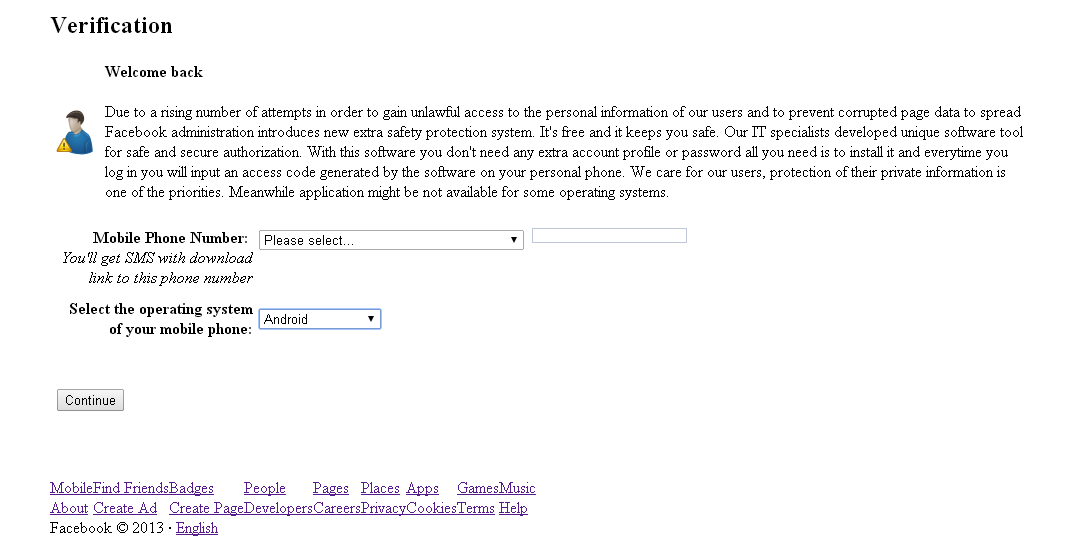

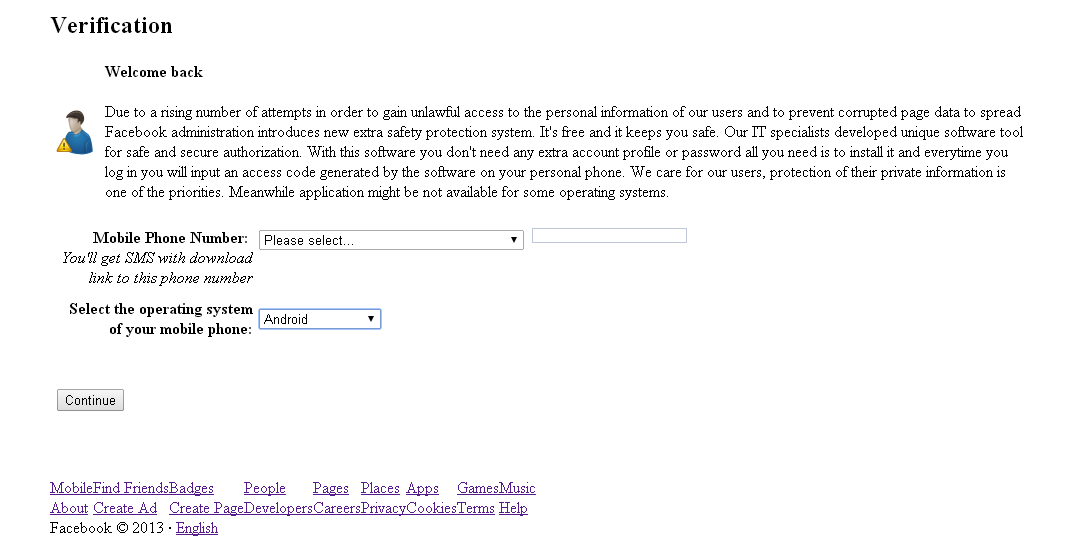

Another, more recent, attack also involves elements of Scareware along with elements of another social engineering based attack – fake apps. A popular mobile banking mRAT named iBanking, has recently begun to rely on a clever new of way of deception.

-

It creates a fake Facebook Verification page for Facebook users, prompting users to enter their mobile number in order to verify the Facebook account authenticity (due to a supposed “unauthorized” attempt to access the victims account).

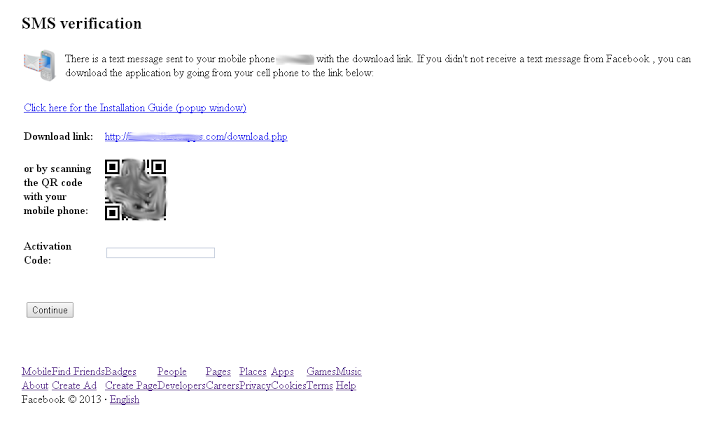

The next step is a fake webpage asking victims to download an app from either a URL or QR code if the autentican SMS fails to reach them (it was of course, never sent). Once downloaded and installed, the mRAT connects to its C&C server.

Next week’s post will cover another aspect of social engineering – Rogue Wifi Hotspots.