The Curious Incident of the Phish in the Night-Time: a Forensic Case Study

Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

On the morning of February 26, 2015, Laurie logged on to her Google account at work and discovered that overnight, someone had used her account as a stepping stone for a total, indiscriminate phishing campaign.

Laurie is the chief administrative assistant of a small venture capital firm. Every new employee, every new customer, every form and every invoice go through her. On that Thursday morning, instead of the usual paperwork, she was greeted with a barrage of replies sent by confused correspondents: “Is this really from you?”, “Should I open this?”, “What is it?”

During the previous night, an email was sent to many of her contacts with the innocuous subject line “PDF from Laurie” and a single link in the message body. Worse still, someone had audaciously responded in her name to several concerned inquiries. “Yes, you should open it,” the forged reply invariably went, “it is an important document that I want you to read.”

The first thing Laurie did was send an urgent email to her entire contact list, warning them not to open any email from her with that subject line. She then notified her superiors and tech support, who took action to mitigate any further damage. Laurie’s system was shut down and air-gapped; all employees were issued new Google account passwords and were switched to two-factor authentication. A few days later, the firm turned to Check Point to conduct a full forensic investigation of Laurie’s system.

The first clue in the investigation did not come from Laurie’s unmounted hard drive, but from Laurie herself. She recalled having received, two days earlier, an email similar to those sent in her name. She had clicked the enclosed link, which opened in her web browser only to show an empty page. This indicated that the malicious link may have been involved in the original compromise of Laurie’s account, and not just in the further propagation attempt. Therefore, our first step was to investigate this link: where did it come from and what was it doing?

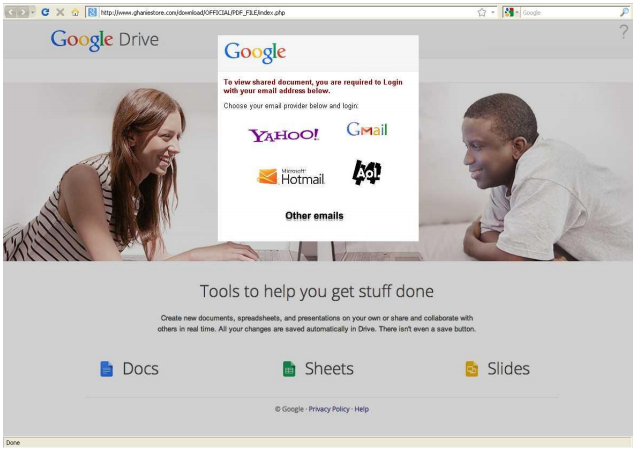

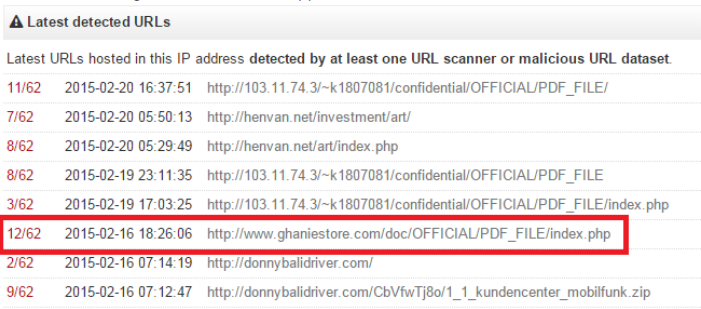

Figure 1. VirusTotal report on URLs hosted in the same IP address as the malicious link sent to Laurie. The link itself is framed in red.

A quick VirusTotal query revealed that the link in Laurie’s email led to a known phishing site, which had been active as recently as a few weeks before the attack. The specific URL was recorded by urlquery.net, which captured a screenshot with the prompt for the victim’s username and password.

The malicious links included in the emails sent by Laurie’s computer led to an identical site on a separate web server, which appeared to be a CPanel-based host that had been hacked to include the phishing site. This URL is blocked by common detections and Check Point products, and the site itself was taken down by a 3rd party some time prior to the current incident.

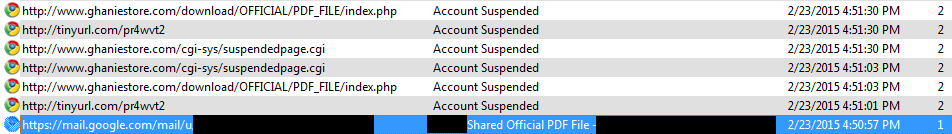

With this lead, we went to work on Laurie’s hard drive using a variety of forensic tools. A search of Laurie’s browsing history revealed two surprising facts. First, Laurie never saw the actual phishing site. At the time of her visit, it was already inactive due to the suspension of its managing account. Second, there were no browser history logs of any emails sent from Laurie’s Gmail account on the local browser, only records for previous emails and for the warning email she herself sent on the morning of February 26. Whoever sent the malicious emails had most likely acquired access to Laurie’s Gmail account credentials and used them to log on from a different computer.

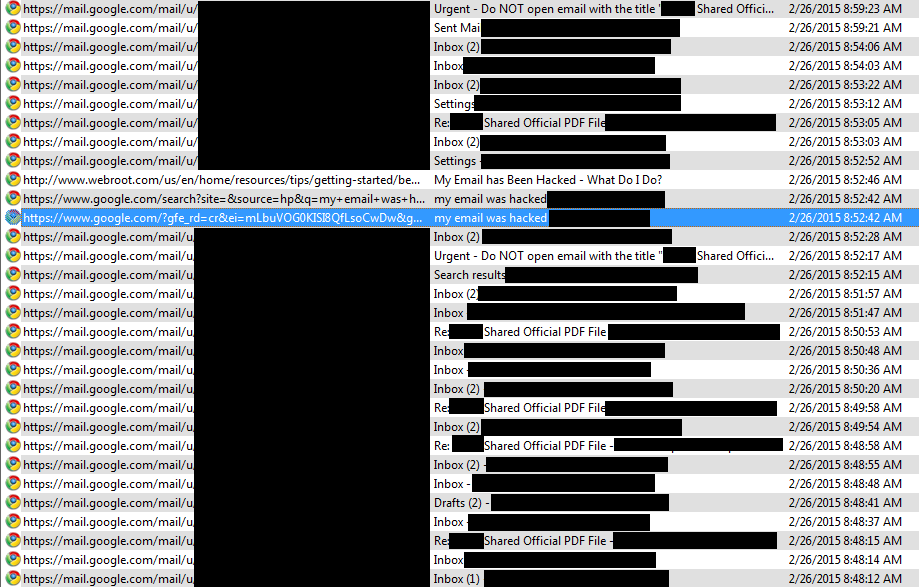

Figure 4. Contacts responding with confusion; Laurie warns of malicious email.

No record of the sent malicious emails themselves.

We looked for evidence that Laurie’s system was infected with malware, and found none. From February 12 (when Laurie received the original email), until the system shutdown on February 28, we could not find suspicious entries in the log of newly created files, nor did we recognize any suspicious modification to the system registry.

Forensic work rarely reaches cut-and-dried conclusions, and this case is no different. During our investigation we encountered several anomalies that, while not alarming, warrant further investigation by the VC firm to ensure that they are legitimate.

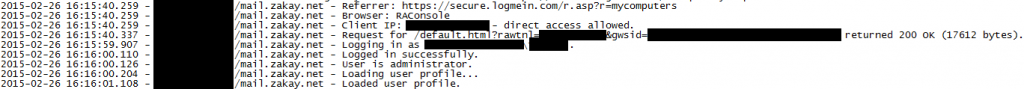

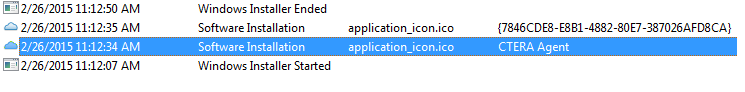

For example, we noted several records of sessions logging on to a remote administration tool on Laurie’s system. The tool was installed, with the firm’s consent, a few months prior to the incident to assist IT operations. According to the logs, one remote administration session took place at noon on February 12. The remote client connected to a local monitoring service and changed various configuration settings. Several other sessions took place on February 26 (after the attack was discovered). During those sessions, the client identified itself using an odd domain (registered to a person from Estepona, Spain) and installed the “CTERA Agent” remote backup and file sync tool. The client IP address in the logs remained constant throughout those sessions, and matches the IP address of the IT service provider.

Based on the evidence available to us, the probability that direct exploitation of the victim system occurred appears low. Occam’s razor applies here: the simplest explanation suggested by the available evidence is the likeliest to be true. Laurie’s credentials were probably obtained as a part of a phishing campaign. That campaign may not have succeeded for the particular email sent to Laurie, but did succeed somehow, somewhere.

In hindsight, the firm could have prevented this incident by taking these steps:

- Increase employee awareness.

- Employees should be suspicious of unsolicited email, even from close contacts. An unsolicited, vague email which does not fit into any conversation thread and instructs you to open a link without fully specifying what’s on the other end should set off alarm bells.

- Employees should think twice or even three times before giving (or entering) their password. Google will not suddenly ask for your password on a whim. If you are asked to enter your password, make sure that there is a reasonable explanation for why (e.g. you had logged out or deleted your cookies). Verify that the domain you are on is legitimate and that the digital certificate is valid. Someone other than Google has no business asking for your Google account password.

- Update browsers on a regular basis. The web browsers used by employees should be periodically updated to the latest version. Later versions of web browsers offer basic anti-phishing protection in the form of blacklists of known phishing sites. While this will not stop more complex attacks or newer campaigns, it is an important and relatively effortless baseline measure to take.

- Two-factor authentication. If possible, two-factor authentication should be enabled. When used properly, two-factor authentication places a significant hurdle between obtaining a user’s credentials and taking control of their account.

What would anyone gain by attacking a small VC firm? Laurie’s desktop computer did not contain anything which, in and of itself, had any significant monetary value. But it did contain a wealth of information that could be used as a pivot for scamming or blackmail, or even offered directly to any interested competitors of the firm or its clients.

If you tell yourself, “Why would anyone attack me, I don’t have anything valuable!” think again. Even if all you have is a laptop for personal use, attackers would be more than happy to make your computing cycles work for them and to use your system as a proxy to hide behind as they attack someone else. If you are part of a business firm, remember that the knowledge you have accumulated equals power, which could be exploited for monetary gain. Where there is a potential monetary gain, it is naïve to expect that no one will come after it.